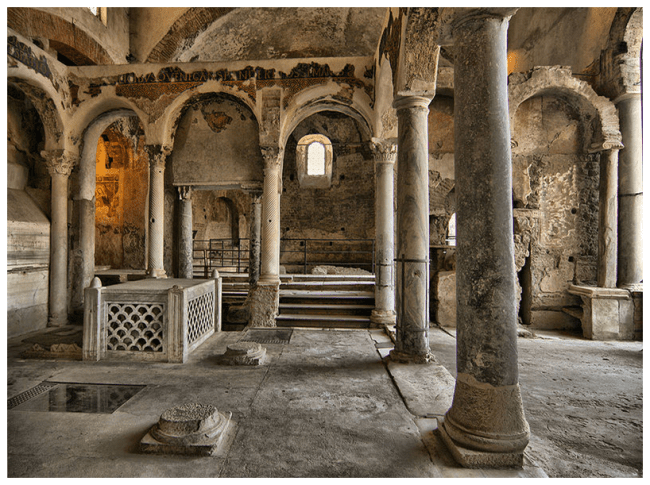

Cimitile is not easy to reach, at least by 21st century standards. It’s on the outskirts of Nola, a town in Campania. When we visited, our bus dropped us off on some distance away from the paleo-christian basilica, and as we walked through town, people looked at us as if to inquire why tourists would want to be in Cimitile. (The name is linguistically linked to the Italian word for cemetery, and it was a burial place even before Christianity arrived.) When we finally reached the archeological site, we found locked gates, but after a few well-placed phone calls, someone came and unlocked the padlock and chain that kept us from our destination.

Cimitile is not easy to reach, at least by 21st century standards. It’s on the outskirts of Nola, a town in Campania. When we visited, our bus dropped us off on some distance away from the paleo-christian basilica, and as we walked through town, people looked at us as if to inquire why tourists would want to be in Cimitile. (The name is linguistically linked to the Italian word for cemetery, and it was a burial place even before Christianity arrived.) When we finally reached the archeological site, we found locked gates, but after a few well-placed phone calls, someone came and unlocked the padlock and chain that kept us from our destination.

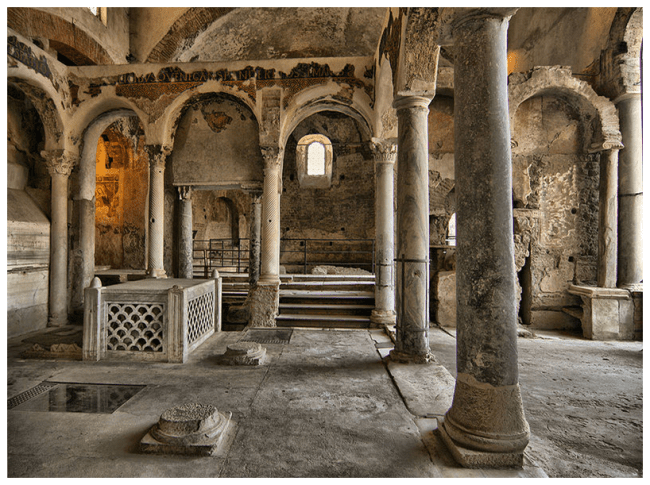

I’m not sure any of us knew what to expect; the town was quaint and unassuming, and the site wasn’t even open when it was meant to be (not altogether uncommon in Italy). But it was the most amazing place we visited anywhere in Italy, in part because the treasures were not behind glass in a museum display, but in situ – right there before us.

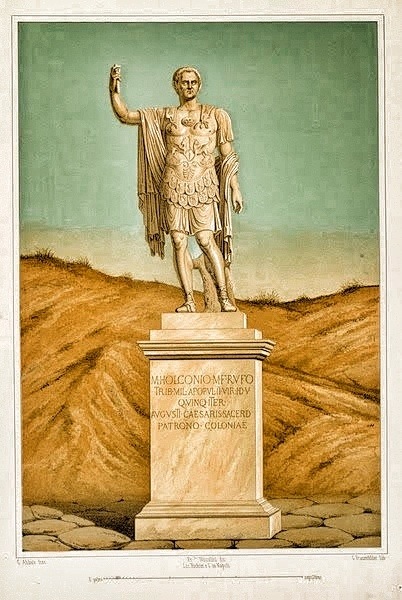

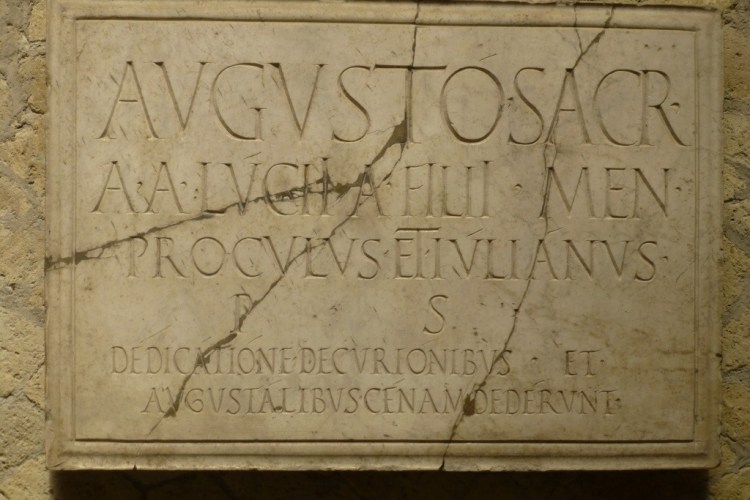

Cimitile was the burial place of St. Felix, a Syrian immigrant who had been ordained and then tortured for his Christian faith. When his father died, Felix sold everything and gave it to the poor (as Jesus instructed in each of the synoptic gospels). Felix became bishop of Nola, died around 250 AD, and his small tomb was visited by a young Christian nobleman from Bordeaux, whose family owned farms nearby. The rich young man was later named governor of the province of Campania in the southern heartland of Italy.

This governor was of the senatorial class, Paulinus, a contemporary of St. Augustine, returned to his wife and his properties in Gaul and then moved to other properties in Spain following the death of their only son. During his time there, Paulinus was ordained as a priest and then with his wife, renounced his formidable wealth and decided to return to Cimitile, where he devoted years to building a shrine to St. Felix.

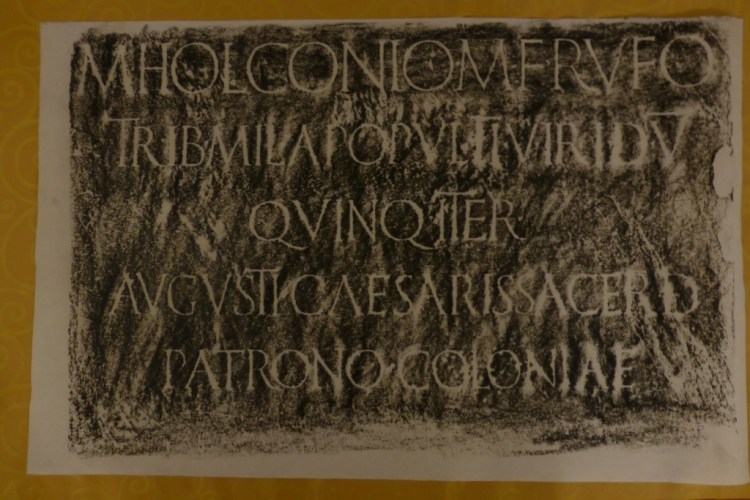

Wax rubbing of St. Felix’s tomb inscription at Cimitile

What as most amazing about Paulinus was not that he was a married priest (not that uncommon in the 300s) or that he was from Gaul. Rather, it was that he was one of the ultra-rich of his day. Many clergy (with notable exceptions like Ambrose of Milan) had come from the middling part of the social scale. Not only was Paulinus on the Forbes List of ancient Rome, he was noble by birth.

But how does one dispose of so much property? You’ll have to read a GREAT book by Peter Brown (Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350-550 AD) to find out the whole story. The short answer is slowly… Paulinus took his immense wealth and created a monastic community at Cimitile. It took more than seven years to create the compound dedicated to St. Felix, which became a major site for pilgrimage. The poor were fed and clothed as they visited the shrine. While Paulinus’s wealth previously insulated him from contact with the destitute, Brown says that “in Cimitile, Paulinus was constantly in contact with the poor.” (p. 235) Brown describes his “open-handed generosity. He provided them with warmth and wine.”

One of the other things that makes Paulinus unique is that he was also a poet of great renown. Not only did he create a monastic community and a shrine, he imbued it with words that entwined his faith with his creation. Paulinus wrote,

For this hope does not abruptly deprive us of our possessions. If it prevails and faith conquers, it changes for the better and transforms our wealth according to God’s law, making it no longer brittle but eternal, removing it from earth and setting it in heaven.

Again, Paulinus draws on the synoptic gospels. Here is Luke’s version: “Make purses for yourselves that do not wear out, an unfailing treasure in heaven, where no thief comes near and no moth destroys. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” Seldom in the history of Christianity do we see such a bold example of renunciation of immense wealth.

The frescoes at the shrine, from the 9th century, are also instructive. The scenes of salvation are “this worldly,” unlike many images we’ve come to think of. Below are two biblical scenes of salvation: Jesus calling the disciples from their nets and Jonah and the great fish.

Jonah and the “whale” are at the bottom right, below the missing fragment of plaster.

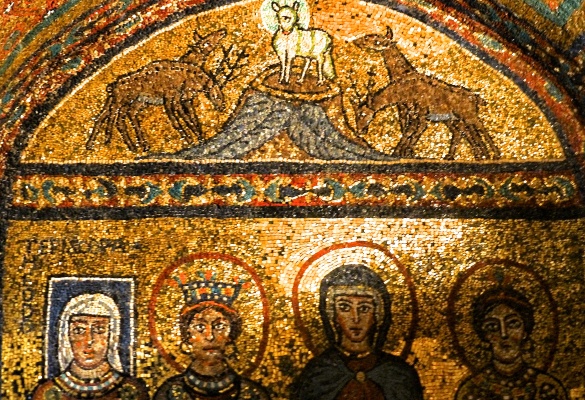

These frescoes are just right there in the chapel (away from the weather, but only just), and they are 1,200 years old! The most moving frescoes for me, however, were earlier ones that I found under the alcove arches across from the tombs of Saints Felix and Paulinus. They are almost invisible at first. As one looks closer, one sees the faces of early Christians – part of this incredible monastic community, perhaps – looking out to us across the ages. Men and women who share a faith in God that is in a lineage with our own.

We have the words and the monastic settlement of Paulinus, but we have the faces of these anonymous Christians, which I find incredibly moving.

Look into the eyes of these early Christians and try to imagine what they experienced. Consider their faith as it was coming to this part of the world. For us Christians in the West, they are our ancestors in the faith. Look into their eyes and imagine what they might say to you from across the ages.