One of my mentors, John Dominic Crossan, said that the church on Torcello was not to be missed. It is the oldest church in the Venetian Lagoon (639 AD) having been settled by dry-landers fleeing barbarian invasions in the in the fifth, sixth, seventh…centuries and settling in the marshlands. In fact, that is the reason Venice exists. It was not a Roman settlement, but was a refuge for people from the Veneto seeking refuge.

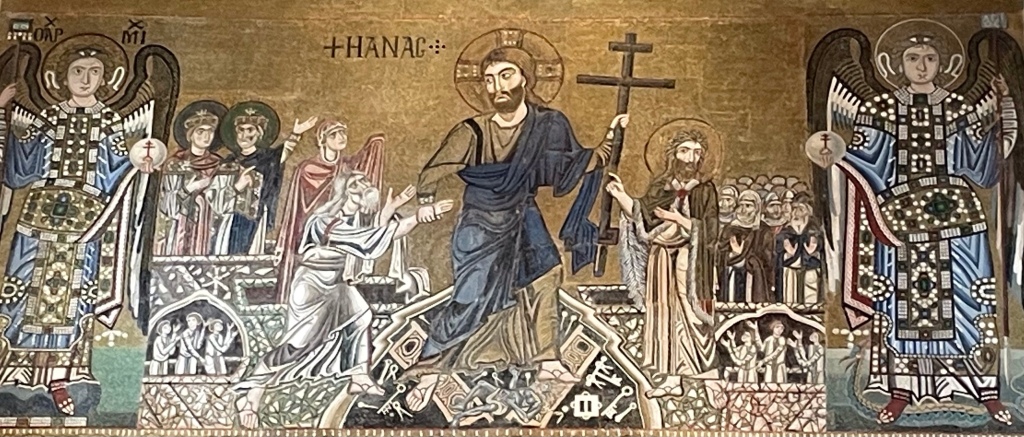

Dom is probably most fond of the basilica on Torcello because it has an immense anastasis — a representation of the resurrection being a communal event in which Jesus empties the underworld, including all of the folks like Adam and the prophets who hadn’t had the advantage of knowing Jesus, the “second Adam,” (and accepting him as their personal Lord and Savior 😉) There is a tradition called “the harrowing of Hell,” in which Jesus descends into the netherworld and releases souls during the days between Good Friday and Easter Sunday. I’ve noticed that sometimes art in a given location will include both the harrowing of Hell and also the empty tomb. But sometimes, as at Torcello and in the Byzantine east, one sees just an anastasis.

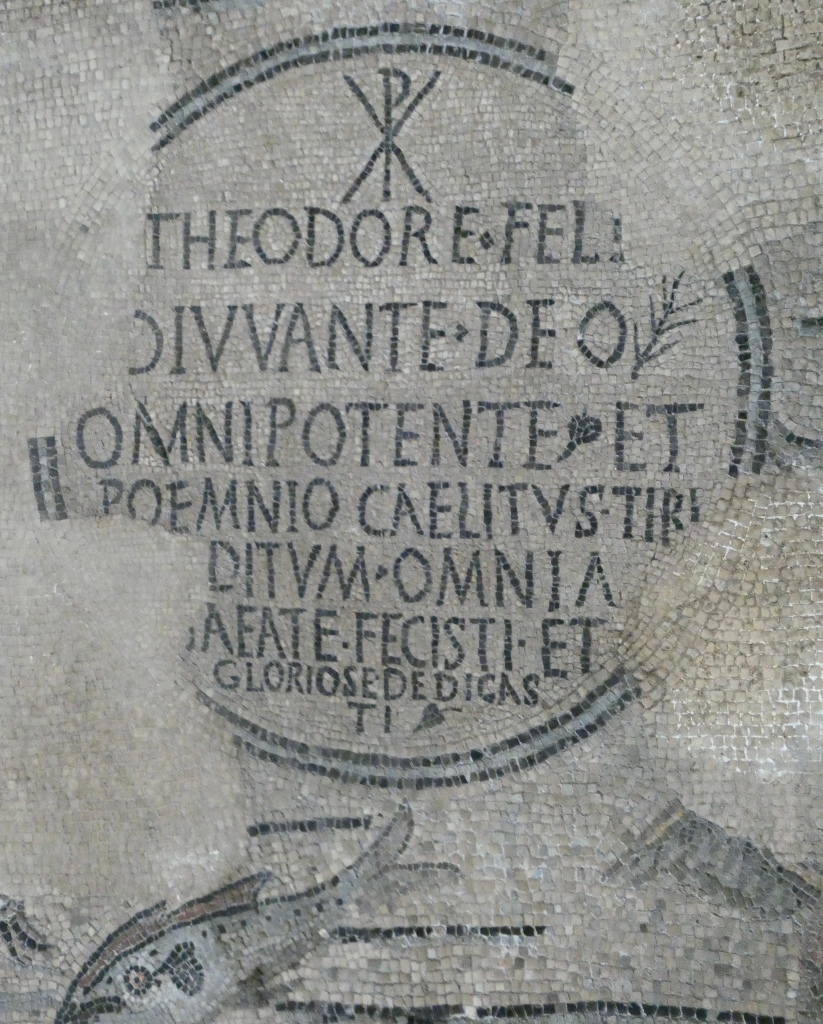

When there is no empty tomb representation, it signifies an eastern way of thinking about resurrection. (See Dom and Sarah’s fine book, Resurrecting Easter to learn a whole lot more about this!) And this is magnificently the case on Torcello. Since it is such an early offshore church, I took the risk of taking photos while the guards either had no sight lines to me or weren’t looking. (I used my iPhone to avoid suspicion, so the photos don’t have the resolution they do when I use my camera.) It is a real buzzkill to hear someone scoldingly shouting “No photos!!”

ASIDE: There is no reason on God’s green earth that they should prohibit photos. It doesn’t degrade the mosaics (and one of their frescoes was in direct sunlight!) and if it because it is such a scared place, why does almost every church allow non-flash photography? If they (and the catacombs) were really serious about not photographing their walls, they could easily provide a website with jpegs available for public use. But I digress…

So, let’s do some SAYS, MEANT, MEANS with this image.

SAYS: It is a Byzantine mosaic of the late 12th or early 13th century. There is no “empty tomb” imagery present. Within the image Jesus is standing atop the broken gates of the underworld and typical of iconography of the anastasis, there are locks, keys, and tools under Jesus’ feet. (Look carefully at the image of Hades: tiny, shriveled, headless.) Jesus has his hands on Adam’s wrist, with Eve following close behind.

MEANT: Jesus is victorious over the grave…not just his own grave, but the graves of all time and all people. God’s “no” to death isn’t simply for Jesus, but extends to all of humanity (at least until we get to the Last Judgement below!).

MEANS: What does this image of resurrection (probably not what you saw in Sunday school or have heard preached every Easter) say to you? How is it different than the empty tomb stories that you’ve heard across the years? Perhaps you interpret the resurrection metaphorically, and if so, what does the anastasis say to you that may be different from what you’ve thought about resurrection since you were young? For me the image insists that Jesus is in charge and powerful, in fact he is “the Lord of the living and the dead.” It has some good news that resurrection wasn’t just a one-off for Jesus coming out of the tomb and leaving it empty, but that ultimately, we all rest in God, who is not only the one in whom we “live and move and have our being,” but also in whom we die, that even past the moment of death, we are with God.